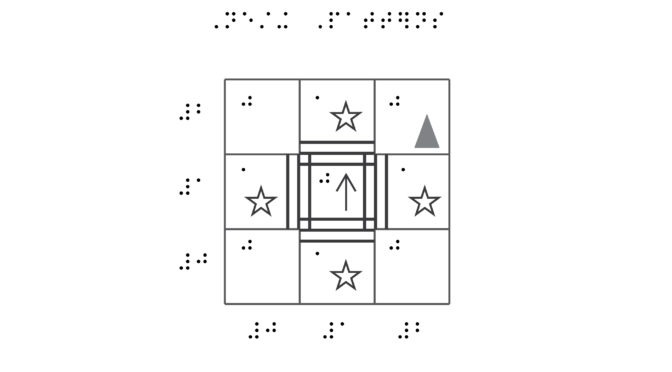

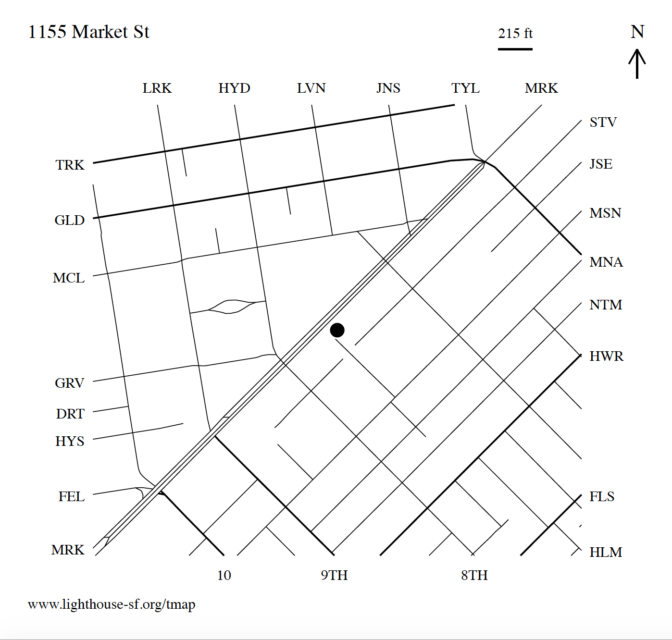

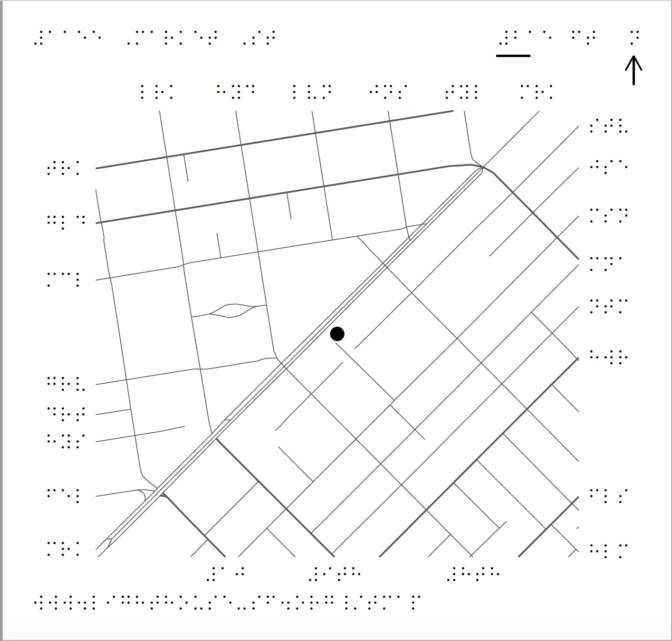

Today San Francisco’s LightHouse for the Blind announced a collaboration with Apple to make learning to code more accessible to students who are blind or have low vision. LightHouse’s Media and Accessible Design Lab (MAD Lab) has created Swift Playgrounds Tactile Puzzle Worlds compatible with Swift Playgrounds, a free, fun and accessible iPad app aimed at teaching students to code. The MAD Lab has designed 47 tactile layouts corresponding with the 3D puzzle worlds found in Learn to Code 1.

These tactile graphics enable students to better orient and navigate their way through Swift Playgrounds by touch. The materials supplement the accessible in-app coding experience, and include Unified English Braille (UEB) and large print text, with high-contrast and embossed tactile graphics in order to be universally accessible. The collaboration is all part of Apple’s Everyone Can Code program, an accessible curricula aimed at bringing coding into more classrooms.

“I’m not going to be one of those people who’s being told ‘No, you can’t do this because you’re blind,’” says Darren, who was an early blind user of Swift Playgrounds.

Darren, a senior at Texas School for the Blind in Austin, learned about Swift Playgrounds at Coding Club, an evening program facilitated by his school. TSBVI was one of the first schools to begin offering the Apple coding program to students. It was a fortunate discovery for him — especially in a world that often assumes a blind person can’t learn to code.

Darren first pursued his dream of learning to code at a public high school, but the online coding module used in his intro-level class was not accessible. As a result, the school offered him a cumbersome accommodation: the teacher assigned a fellow student to read Darren the lines of code and type his responses. For Darren this was a considerable barrier: not only did he not get hands-on experience, but he had to work at someone else’s pace.

“I think the teacher knew it was frustrating,” Darren says, “but he wasn’t entirely sure how else to make it accessible.”

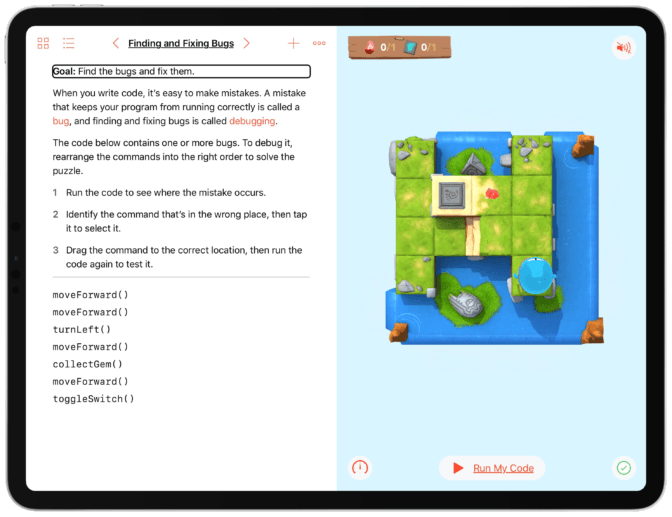

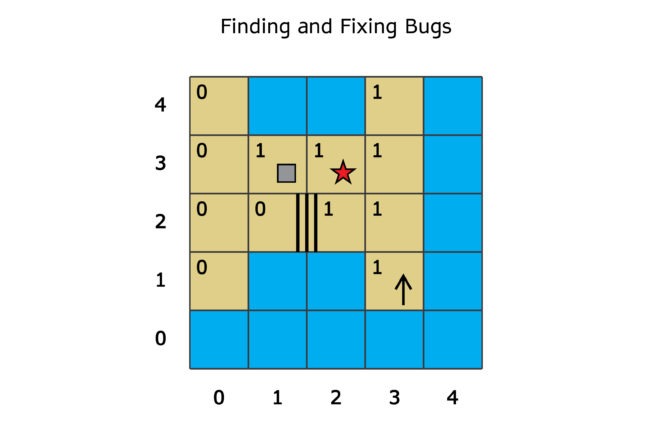

When Darren first heard that the Swift Playgrounds app was accessible, he downloaded it onto a rented TSB iPad, eager to dig into a new world of coding. But as his new coding class started and he began to work his way through the “puzzle worlds” that make up the game’s levels, he felt he would benefit from also having tactile feedback.

“At first it was confusing because I didn’t know how the world looked,” he says, without a hint of irony. Thanks to Apple’s commitment to accessibility, Darren could use Swift Playgrounds with VoiceOver, Apple’s built-in screen reader, but he needed a way to explore and experiment in the 3D puzzle world – collecting gems, toggling switches – and in order to do that, he needed a mental map of the physical layout.

Enter the MAD Lab

Meanwhile Apple was working on a solution – with help from the LightHouse’s Media and Accessible Design Lab.

Building off years of experience creating tactile maps of cities, universities and cultural landmarks for blind and low vision explorers, the MAD Lab is proud to present a new accessible media experience by designing a tactile experience that corresponds to a dynamic 3D puzzle world. Mapping the visual layouts of each puzzle world and enhancing them with cartographical elements to optimize for comprehension, the LightHouse is proud to partner with Apple to further the blindness community’s tech literacy, around the world.

Putting the tactile worlds to good use

Once the Texas School staff got their hands on the guides, everything changed for Darren. “We were creating graphics,” his teacher, Susan O’Brien says. “We had 3D printed some of the switches, the toggles, the portals, but then when we saw your maps, we were like ‘oh my gosh, this is so much better than what we’ve been doing.’”

Today, Darren uses the tactile layouts map to orient himself to the world, then he’ll talk through the commands, then go back onto the iPad and really start to do the coding. “We saw him develop a workflow,’ says O’Brien. “Finding that workflow that’s best just for you – that’s so crucial for everyone, blind or sighted.”

For Darren’s part, he’s now working his way through the game, twice as fast as before. “I’m extremely happy that I don’t have to rely on someone else to get the job done now.”

Downloads for students and educators

Teachers or organizations who have access to braille embossers can download the tactile graphics files to print themselves, or if an embosser is not available, can order beautifully printed, embossed and bound hard copies through the LightHouse’s Adaptations Store.

Swift Playgrounds is a revolutionary iPad app that makes learning programming language Swift interactive and fun. It requires no coding knowledge, so it’s perfect for students just starting out.

Download the Swift Playgrounds app for free app on the App Store

Download Swift Playgrounds Tactile Puzzle Worlds for free via Apple