Tune in to the livestream of Ahmet’s crossing!

Ahmet Ustunel won the Holman Prize for Blind Ambition in 2017, becoming one of the prize’s first three recipients. On July 21, he will complete his project in one great flourish: with a solo trip across one of the world’s busiest shipping channels, alone in a kayak. LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired in San Francisco announced the 2018 Holman Prizewinners this month, and we will continue to provide updates on the projects of our other two prizewinners from 2017, Penny Melville-Brown and Ojok Simon, as the summer continues.

In the hills of Istanbul, there aren’t always sidewalks. To get to where you’re going, you have to hug the sides of the busy streets, sharing the roads with the cars, bicycles and lifeforms of this city of 15 million. This is Ahmet Ustunel’s summer commute, a 90-minute trip that he takes each morning to the very Southeastern tip of Europe to the shores of the mid-city shipping channel known as the Bosphorus Strait, where he practices for his solo journey across the waterway at the end of the month.

Ahmet is starting to get a bit nervous. It’s early July, hot every day and this blind San Francisco schoolteacher has returned to his native ground to begin, quietly, the greatest adventure of his life. For the last seven months, he has lived on the water – venturing from his home back in San Francisco to seek out the Bay Area’s aquatic offerings nearly every week, sometimes with friends and sometimes, alone. He’s not nervous on the water. But he also knows that technology is a fickle friend. And with the devices he relies on to navigate, technical failure is a likelihood.

“I feel like I’m working full-time,” says Ahmet. “I’m pretty much working 16 hour days. Including the commute, my training takes eight to 10 hours. Then I take care of paperwork, permits so that we can film, logistics, finding a support boat.” Ahmet’s journey, it turns out, is more a test of planning and anticipating challenges than strength or skill.

Sound travels differently on the water. It slows down and dances lazily in the cool pocket of air just above the water’s surface. This can have an amplifying effect, making sound appear closer from great distances, but it comes with a price: sounds also stretch and bend, ricocheting off choppy breaks and skipping along with deceptive ease when the water is calm.

For a lone blind boater, this is a real consideration. “You can’t really pinpoint if something is going to hit you or pass by,” Ahmet tells me from Turkey earlier this week. It’s 10 p.m. there, but I can hear the sounds of the city behind him over the phone, like he’s out taking a stroll. “The sounds stretch out on the water. That’s the problem,” he says. “It’s not like listening to a car and realizing if you are in its way or not. And if it’s a big boat, most of them have their engines on the back so you hear the sound farther, but the boat is actually closer. You can have a 70 meter boat, like the size of a football field, but because the engine is on the back the boat is actually 70 meters closer than it sounds.”

One of the busiest waterways in the world, the Bosphorus is a highway for ships threading the needle between Europe and Asia. Ahmet was raised in this industrial landscape. Totally blind since age 3, Ahmet grew up on these shores, swam on these beaches, and most of all, dreamed of a day when he could captain a boat. Decades later and fully assimilated to life in America, wending his way through the bustling and at times chaotic infrastructure of Istanbul makes him feel a bit rusty.

When it comes to heavy traffic, the strait carries more than 40,000 boats and ships a year (approximately 110 a day). “I’m not afraid of capsizing or ending up in the water,” he says. “It’s fine. But the boats – they don’t pay attention. Most of the time they don’t look around. They assume that you are going to get out of their way, and that’s the only thing that scares me on the water.”

In an uncharacteristically theatrical move, Ahmet attaches his white cane to his kayak, sticking up right out of the stern. But the cane, which serves as a valuable navigation tool on the streets, is useless in water.

At 10 a.m. on Saturday, July 21 (12 a.m. on Friday night in Pacific Time), Ahmet will attempt the journey he’s been planning since applying to the Holman Prize in January 2017 – here’s how he’ll do it:

Ahmet’s vehicle of choice is a Hobie hard-shell kayak, with a foot-paddle system that allows him to power the craft by pedaling, like a bicycle. In his left hand, he’ll hold a lever that runs down to the kayak’s rudder and allows him to steer and keeping his right hand free to manage his navigational devices.

The tech, which Ahmet developed with a team of volunteer engineers (many of whom also work at AT&T, in Atlanta) is fairly simple, but comprised of a delicate orchestra of devices that weren’t necessarily made to work together. There’s a talking depth sensor that Ahmet has repurposed to identify objects at a horizontal rather than vertical distance; a non-visual compass of sorts called Mr. Beep (originally an aid for blind rowers), which Ahmet has hacked to send vibrating feedback to his left or right hands to show direction while keeping his ears free to listen to traffic; and of course his phone, which will mostly function to livestream his progress to the world.

Ahmet’s friends on land will help him scope out the strait the morning of the launch, settling on a time when there’s the least likelihood of him paddling straight into a nautical traffic jam. But once Ahmet sets his boat in the water, he’s on his own, first paddling out 20 or 30 meters by hand, then pedaling by foot. The current is strong on the straight, stronger than northern California’s Tomales Bay, where Ahmet has practiced on his own in the past.

When he reaches the shipping highway in the middle, he’ll have to decide if it’s safe to cross. That’s when things become a bit risky. In case of emergency, Ahmet has developed a three-tiered code system with his support team, who could radio him at danger level 3 to let him know he’s on a collision course with a ship. At that point it’s still his job to get out of the way, and the team won’t interfere with any navigational needs or warn him about stationary objects.

When I asked him what he’ll do when he reaches the other side, Ahmet is characteristically humble: “I don’t know, have a tea.” Then, assuming all is well, he’ll hop back in the kayak and return to the other side (an unassuming and unpublicized second crossing).

The support team trailing Ahmet in the distance (he’s told them to stay far enough away that he can’t hear their engine) will include Sarahbeth Maney, a Bay Area photojournalist who has followed Ahmet through his whole journey and is working on a documentary about Ahmet called “The Blind Captain”, and Dilara Yarbrough, Ahmet’s wife and a Criminal Justice professor at San Francisco State. On the shore, Ahmet will be greeted by a contingent of enthusiastic friends and Turkish journalists, including publications such as TRT World, who have taken interest in his endeavor.

The team won’t be the only ones following him, though. Ahmet’s crossing will be live streamed through his Blind Captain Facebook page, and sighted map enthusiasts should be able to track his GPS location at his engineering team’s tracker page. The map will give those who are following along visually a sense of how efficiently he moved across the water, and the Holman team at LightHouse will recap his progress on the LightHouse Facebook Page as well.

Finishing the journey won’t change the course of history or go straight into a Guinness book, but Ahmet knows that the symbolism of his solo trek is powerful for the general public and other blind would-be adventurers alike. He has visions of the modified Mr. Beep becoming a mainstay for blind navigation of all sorts. Late last year, in an interview with Red Bull, Ahmet suggested that the hacked tech he developed could also work for blind runners, surfers, cyclists and others who need intuitive non- visual guidance.

Returning to Turkey has become a tradition for Ahmet and his family, and he has a group of blind friends and colleagues there even bigger than the network he has in the states. Next summer, he hopes to return to do something “a bit more social,” such as passing on his kayaking skills and love for the outdoors to other blind children who are nursing the same dreams of piloting their own destiny.

About the Holman Prize

In 2017, San Francisco LightHouse for the Blind launched the Holman Prize to support the emerging adventurousness and can-do spirit of blind and low vision people worldwide. This endeavor celebrates people who want to shape their own future instead of having it laid out for them. In early July, we announced the 2018 Holman Prizewinners — congratulations to Stacy Cervenka, Conchita Hernández and Red Szell.

“We are thrilled to be able to continue the Holman Prize for a second year,” says LightHouse CEO Bryan Bashin. “These three new prizewinners represent a wide range of ambitions and life experience: from tackling social obstacles to to huge tests of physical and mental fortitude, they reflect the diversity and capability of blind people everywhere.”

Created specifically for legally blind individuals with a penchant for exploration of all types, the Holman Prize provides financial backing – up to $25,000 – for three individuals to explore the world and push their limits. Learn more at holmanprize.org.

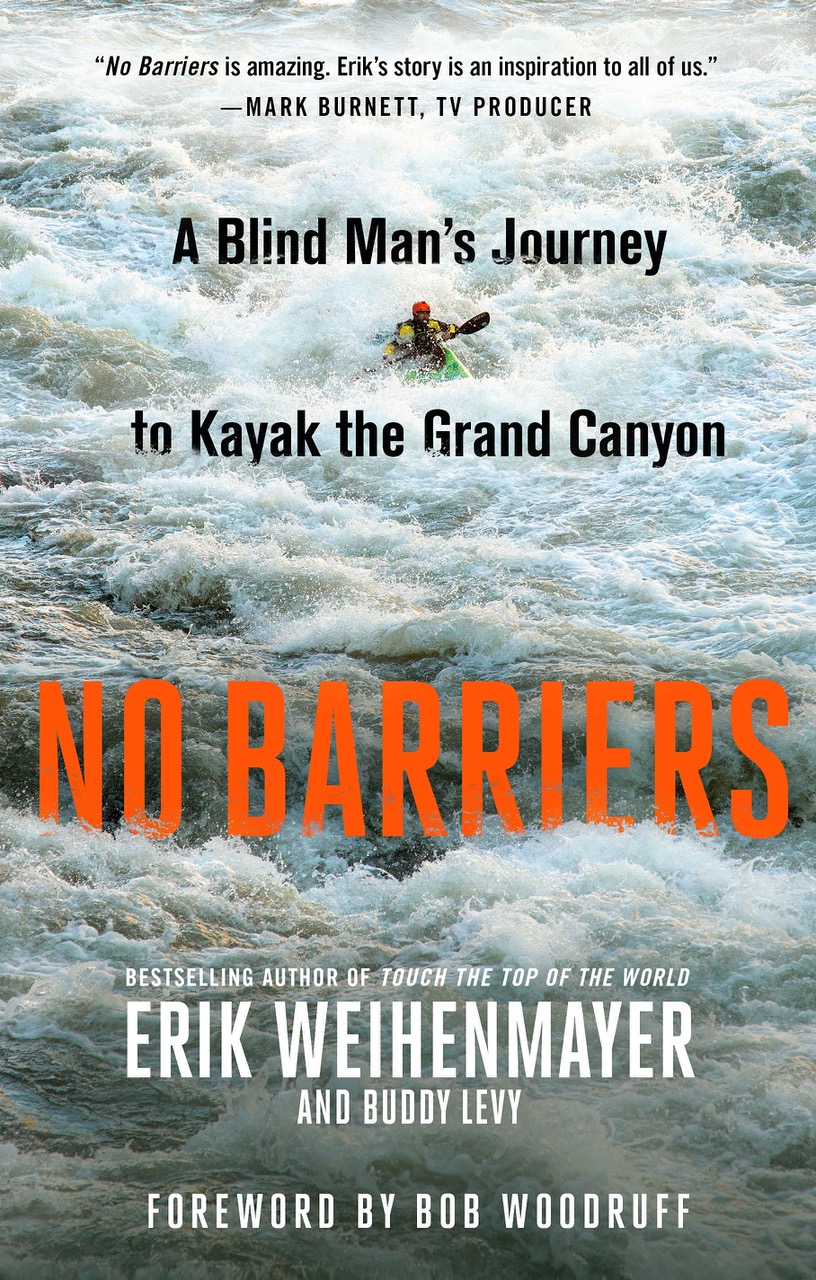

On May 2, we’re welcoming blind explorer Erik Weihenmayer as our guest for the

On May 2, we’re welcoming blind explorer Erik Weihenmayer as our guest for the